Dirty Laundry

Our relationship with cloth is visceral and primal -- we are swaddled in it at birth and aside from a caregiver’s embrace, fabric is our first experience with touch and comfort. Who of us, in times of turmoil, has not pulled the covers over our head, or wrapped ourselves in a loved one’s shirt, sweater, or scarf? To be covered is to be comforted, protected, and hidden. To wit, cloak is both a garment and an action to shield from sight.

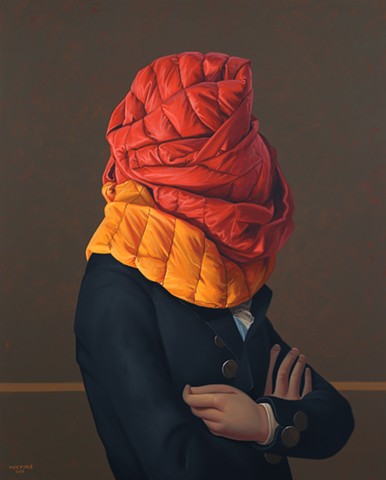

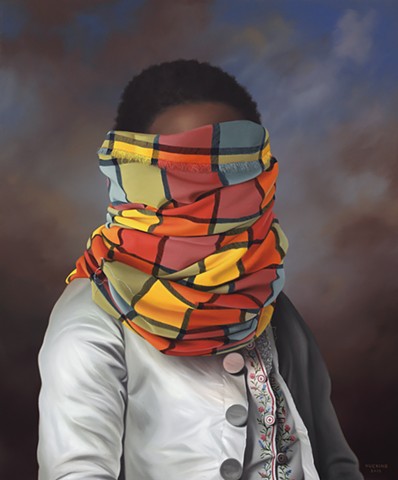

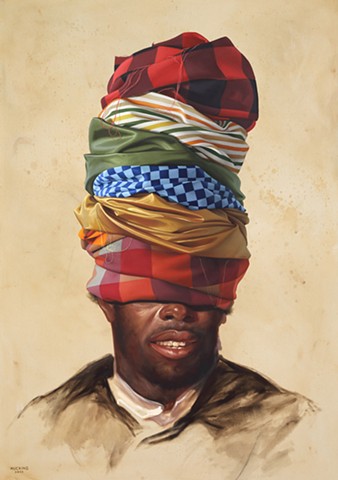

We use cloth to conceal, but also to express, selectively, based on how we see ourselves and how we want others to see us. Of course, we don’t express all facets of our identity, some things we hold near out of habit, nature, or fear of ridicule. We all have dirty laundry, literally and figuratively. Dirty laundry, the phrase, is defined as personal, or private affairs that one does not want made public as they would cause distress and embarrassment. Dirty Laundry, the series, employs contemporary fabrics painted over traditional American portraiture to explore questions surrounding what, how much, and how well we share and hide.

In these hand-painted recreations of historic works, fabrics are staged on a model in the studio, lit from the same direction and with the same temperature as the light source in the original painting, then drawn into the final composition. Bold, bright, and colorful fabrics cover all, or significant portions of the portrait. Viewers get few clues about the sitters, save an exposed hand, piece of jewelry, or beloved pet, all superficial details chosen to be revealed. Only in a painting’s title do we learn the subject’s identity, anything more that might be known about these people remains hidden beneath piles of cloth and clothing so ubiquitous it could be our own. The towering fabric head dress on "Bashi-Bazouk" and heap of shirts on "Mary Greene" appear poised for imminent toppling, while others, like those enveloping "Mrs. Freeman Flower" and "Portrait of a Lady" look well-secured. This leaves us wondering what is hidden and what might be revealed should the fabrics fall, but also probes on how our perception of these subjects might change once uncovered and which subjects we’d prefer to be.

Dirty Laundry gives us the opportunity to question the security of our own concealments. What are we concealing from ourselves and others? What would it mean for the parts we conceal to be exposed? How would others react to our dirty laundry?